“My son has suffered but yet he doesn’t complain…He deserves a chance at having answers or paving the way for answers for others.”

“As I sit to summarize [daughter], I find myself tearing up and very emotional. Nine years of chronic medical crisis’ and so many failed treatments leaves so much to recap”.

“As parents we want nothing more in the world to figure out what is going on with her...She has determination that is mind blowing, she is our hero.”

These are the words of parents who have been on a long and exhausting journey to find a diagnosis for their children with mystery illnesses and finally turn to the Undiagnosed Diseases Network (UDN), hoping for answers. The UDN, established by the NIH Common Fund in 2014, strives to find diagnoses for patients with undiagnosed rare/ultra-rare disorders. Collectively, these disorders affect 1 in 12 Americans, exerting a significant personal and societal impact. Families are devastated by the manifestations of these disorders which are usually early in onset and severe in nature. Not having a diagnosis makes the patients ineligible for treatments, clinical trials and medical surveillance. Furthermore, since ~80% of rare/ultra-rare disorders are genetic in etiology, the lack of a diagnosis also leaves uncertain the chances of the disorder recurring within families. The mission of the UDN is to find diagnoses for these patients, thereby improving their management as well to advance the science of rare/ultra-rare disorders.

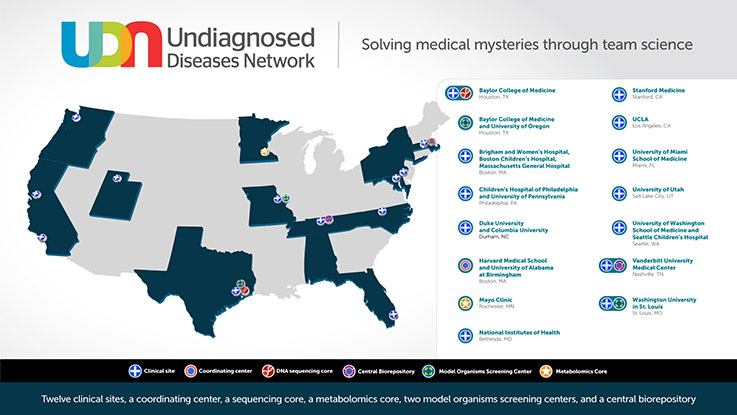

The UDN consists of 12 clinical sites across the United States (of which Duke is one), supported by a Coordinating Center, and research cores including sequencing, animal modeling and metabolomics, to facilitate diagnoses, as well as new disease gene discoveries. The Duke clinical site consists of the Principal Investigator Dr. Vandana Shashi, genetic counselors Kelly Schoch and Rebecca Spillmann, social scientist Dr. Allyn McConkie-Rosell, clinical research coordinator Nicole Walley, and team physicians Dr. Khoon Tan and Edward Smith.

Patients can apply to the UDN anywhere from within the USA and outside. The Duke site receives applications from the southern and midwestern regions of the USA. The Duke clinical site absorbs all the costs of the UDN evaluations, understanding the immense burden that families already face with these disorders.

Every UDN patient undergoes a customized evaluation, tailored to their individual manifestations, including additional comprehensive medical evaluations, innovative analyses of genomic variants, and collaborative science including cutting-edge lab assays and animal modeling. This unique n=1 approach leads to diagnoses when multiple prior diagnostic attempts have been unsuccessful. Indeed, 2/3 of UDN diagnoses occur due to resources that are not available in clinical settings.

The diagnosis rate of the Duke site is the highest in the network (44.1%), compared with the UDN-wide diagnosis rate of 29%. 252 patients having been evaluated thus far, and 15 new disease genes have been discovered due to the efforts at the Duke site, again the highest in the network. Another 10 are currently being investigated.

A distinctive focus of the Duke clinical site is to understand the psychosocial toll that patients with undiagnosed disorders experience. The team works in partnership with the patients and the families, with compassion, as noted by a recent parent’s post-evaluation survey response, “UDN has been a blessing for our family. The level of care, expertise and professionalism was expected by working with a facility like Duke, but what we didn't expect was the other impressions made on us by the UDN network. We felt like for the first time we were part of a "family" that was REALLY listening to our concerns, taking time to get to KNOW our son not just for diagnostic purposes but for everything that makes him who he is, and looking at his case as a whole.”

During the course of the UDN, the Duke team also observed that ~30% of parents whose children were referred to the UDN do not apply, despite being reassured that all UDN evaluations would be free and their travel and accommodation would be paid for. The parents who do not apply are more likely to be non-White and to reside in underserved rural counties. “It’s not fear of genetic research,” says Dr. McConkie-Rosell about the reasons for their non-participation. The parents report practical barriers such as childcare/time off work and also psychological factors such as being emotionally exhausted by their long quest for a diagnosis. Yet, these parents want a diagnosis as much as parents who do apply to the UDN. The team is now actively working to mitigate the practical barriers (using telehealth as a first step), with a future goal of addressing the psychological factors, to ensure equity in participation in the UDN.

The UDN is a national resource for patients with undiagnosed disorders, and this translational network is on the cusp of completing Phase 2 of its activities, with an uncertain future. The Duke site is continuing to pursue innovative paths forward to continue this critical effort, including increasing access to genomic medicine for patients in underserved areas and therapeutics for ultra-rare disorders. As Dr. Shashi says, “Working alongside the patients and their families has underscored how important the UDN is in providing long elusive answers and paths forward to the families and we are committed to continuing these efforts.”